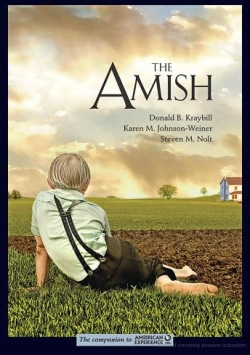

The Amish by Donald Kraybill, Karen Johnson-Weiner, and Steven Nolt is a comprehensive look at the Amish culture and religion. It is well-researched and well-written and is divided into five sections and twenty-two chapters. Each chapter begins with an extract of the material to follow. I am focusing my review on several sections that stood out from the rest of the material in the book for me.

The extract of the first chapter begins with a glimpse of how a “national crusade for educational progress”… had a bump on the back roads of rural America” when in the fall of 1954, some 100 Amish people were arrested for refusing to send their children to school beyond the eighth grade. I thought this chapter was going to be about Amish education, but it was actually about how the Amish are a thriving people and their constant struggle with modernity. This is the only chapter in which I felt the extract did not match the contents of the chapter. All the rest of them were right on.

In the second section there is a chapter on religious roots that I consider one of the best in the book — from the extract to the end. For so long, I have been trying to put into words the Amish belief system, and I always feel I fall short. And here it is, well conveyed. The chapter begins with an Amish church service being held in the upstairs of a barn, and just as the people in the congregation turn to face their benches to pray, the host rises and pulls the barn door shut. When a visitor asks why he did that, the elderly bishop states, “Because Jesus taught us to pray in private.” This conveys the humility of the Amish faith. Theirs is also a faith steeped in martyrdom and deep traditions, which is best described in the following chapters on sacred rituals in the gathered community, the Amish way, and their symbols and identity.

In the third section, there is a chapter called “Rumspringa to Marriage,” which is another one of my favorite chapters in this book. I want to say “Bravo!” to the authors for challenging seven different myths, by giving real information about what rumspringa is and is not. For example for “Myth Two: Parents encourage their children to explore the outside world,” the authors state “Some pundits say that the church has established a cultural ‘time out’ for that purpose, but this is simply false.” They quote an Amish woman as saying, “Rumspringa as people talk about it is a lie. What group of parents that love their children would say, ‘Go out and do whatever you want and decide whether you want to be like we raised you’?” After reading this chapter, I no longer feel so alone in trying to shatter the myths about rumpspringa. The one thing I would have added is that there are several Amish communities that require their young people to become members of the church before they are allowed to date. That gives the church authority over the young people’s actions, which does not allow for any relaxing of the rules of the Ordnung.

I have pondered the reason why the people in mainstream culture have latched onto the idea that the Amish allow their young people a time to make a conscious choice about whether they stay or leave. I think there is a desire to superimpose our values on their culture. We are the ones who value choice and therefore deem the Amish a better society if they give their young people a conscious choice. But that is not at all what the Amish are about. Their culture is about sacrificing personal freedom for the sake of the community. Having a conscious choice about being Amish is the polar opposite of the experience of most Amish youth who know they are expected to join the church, be baptized, marry, have and raise children in the same faith as their parents, their grandparents, and many other generations before them and live out their lives in an Amish community. If they do so, they experience a close community throughout their lives, while we get our personal freedom. As the Amish put it — it’s impossible to have both.

The chapter on Amish education is literally the only chapter in the whole book with which I disagree, almost completely. I would have liked for the authors to grapple with the ethical and moral dilemmas that result from exempting one religious group from compulsory education and child labor laws. It was argued in the 1972 landmark Wisconsin v. Yoder Supreme Court case that the Amish culture would not survive if they were bound by the same laws as everyone else. This begs the question of whether it is ethical or moral for the Amish to deprive their children of an education beyond the eighth grade so that the culture can survive. This is not unlike many of the other aspects of Amish culture, in which they are held to a different standard than the rest of society.

Rather than deal with these issues, the authors focus on the long and contentious struggle for the Amish to become exempt, the demise of the little red schoolhouse, and the explosion and structure of Amish schools. They also write about teachers, diversity of Amish schools, the academic outcomes of Amish schooling, and “different world, different aims.” Unlike the rest of the chapters, this one feels unbalanced to me.

At the Amish conference in June 2013, one of the authors stated publicly that there are some Amish groups that would like to educate their children beyond the eighth grade, but out of solidarity with other Amish affiliations, they are not doing so. They are concerned that it will cause controversy in more conservative groups because the authorities can point to the Amish groups allowing more education as a way to force the more traditional groups to follow their example. The author may have a point but it’s not the only area in which the conservative Amish struggle with authorities and the liberal groups do not, such as with the issues of triangles on buggies, compliance of building codes, and outhouses.

It took me years after leaving the Amish to realize that level of education is not determined by the Ordnung of the Amish church. The expectation that parents limit their children’s education lives somewhere outside the rules of the church, but is deeply ingrained in the Amish psyche. If it were included in the rules of the church, it would technically be open to debate every six months when the bishop of each church district reviews the rules of the Ordnung because all the members of the church get a vote about whether they agree. It is rare that anyone disagrees, but this point of distinction is still a valid one. It begs the question of why education is a controversial issue if limiting education of children to the eighth grade is not one of the rules in the church.

If I could change anything about the culture that I was raised in, it would be that the Amish educate their children beyond the eighth grade, even if it’s for two more years in their own schools. I think so much good would come of this. If indeed more people leave the community as a result of realizing they have a choice, then the people who decide to stay would have made a more conscious choice to do so.

Overall, the authors did a very good job of looking at two sides of the various issues and they wrote with a unified voice in The Amish. I appreciate that the book as a whole represents an exhaustive amount of research and an unwavering commitment to writing and editing as a team. The end result is a body of work that will be excellent reference material for years to come.

Hi Saloma,

I did not read this book but did see the DVD of it a few months back. I really enjoyed it.

With the scarcity of available land and more Amish folks finding employment outside of the fold it seems an education beyond the 8th grade would be beneficial for some. However, learning a trade through an apprenticeship or simply on the job training offers a solid education, as well. It would be wonderful if the child could choose his/her educational journey. For that matter, it would be nice if the parents could.

In England and Canada there are several Islamic communities that use Sharia courts to handle civil issues within their groups. Though these countries find spousal abuse against the law, in Sharia courts a man can legally beat his wife up to three times a day without consequence. I wonder if there are other groups that are exempt from laws the population at large must obey?

Hi Saloma,

I did not read this book but did see the DVD of it a few months back. I really enjoyed it.

With the scarcity of available land and more Amish folks finding employment outside of the fold it seems an education beyond the 8th grade would be beneficial for some. However, learning a trade through an apprenticeship or simply on the job training offers a solid education, as well. It would be wonderful if the child could choose his/her educational journey. For that matter, it would be nice if the parents could.

In England and Canada there are several Islamic communities that use Sharia courts to handle civil issues within their groups. Though these countries find spousal abuse against the law, in Sharia courts a man can legally beat his wife up to three times a day without consequence. I wonder if there are other groups that are exempt from laws the population at large must obey?

I bought this book although I haven’t read it yet. Nor will I read it all in one setting.

Another book for me to read just as soon as I am done with our summer business and finished with camp crafts as well!

This is awesome!