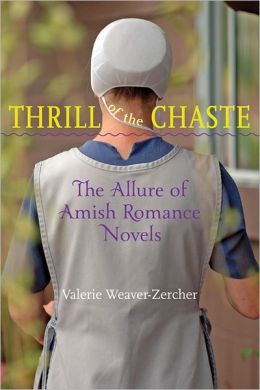

I recently was given a copy of the book Thrill of the Chasteby Valerie Weaver-Zercher, in exchange for visiting one of Dr. Donald Kraybill’s classes. I had known that Weaver-Zercher was studying Amish romance novels, so I looked forward to this publication, for I want to understand the reason for so much interest in this subgenre.

For anyone not familiar with Amish romance novels, they are those books you see in the Christian section of bookstores or in the gift shops of Amish-style restaurants with demure women in Amish garb, some leaning on fences in a pasture, others hovering above an Amish landscape, and still others with a male next to or behind her. Almost invariably, though, there is the proverbial Amish head covering. The reason for this was articulated by one publisher when he said, “You slap a bonnet on the cover and double the sales.”

A friend recently gave me her impression of walking into a restaurant with a rack loaded with Amish novels. She describes her impression, “This is Amish smut!” Given these are clean romances, without sex, or in most cases, without even as much physical contact as lip-kissing, this is an interesting impression, but one I share.

The content of these books are formulaic: the protagonist grows up Amish, she arrives at a place in her life (usually through a crisis) in which she questions the Amish faith, and then she has a conversion experience and becomes a born-again Christian. Somewhere along the line, there is a romance, often one in which she has to choose between an Amish boyfriend and an English one. These stories invariably end happily.

Weaver-Zercher has a humorous description of her friend, Margaret’s, reaction to her research when she tried to explain what she was studying.

… she is intrigued and a little confused. Like several other people with whom I spoke, she thinks at first that I am writing an Amish romance novel. No, I clarify; I am writing about them.

“So let me get this straight.” Margaret pauses, her forefinger raised above her chicken and rice. “You are writing about us, who are reading the books that other people write about the Amish.” It is obvious that this project strikes her as a tad funny, amusing in both its degrees of separation from the Amish and the endless ripples of research it suggests. [Pg. 231]

I enjoyed Weaver-Zercher’s wit throughout the book. She describes her own enjoyment of reading the books this way, “Eager to keep reading my latest Amish romance but unwilling to admit it, I would sometimes tuck the book under my sweatshirt when going to the gym or under a notebook when entering a doctor’s waiting room. … The deeper I got into this project, the more fascinated I became by the surreptitious nature of my Amish romance reading.” I felt like she left me hanging on this question. Perhaps answering this question for herself might have given her insights into the “typical” reader’s interest in these books. She does give us several good insights as it is. One she terms hypermodernity. “The speed, anomie, and digital slavery of contemporary life have sent many readers, weary of hypermodernity, to books containing stories of a people group whom readers perceive as hypermodernity’s antithesis: the Amish.” The other term she uses is hypersexualization in which “sexual discourse, erotica, and pornography are present in almost all aspects of society.” She wrote, “The exponential growth of Amish fiction during the first decade of the twenty-first century cannot be understood apart from these “hyper” cultural developments.”

And when Weaver-Zercher mentions exponential growth, she is not joking. She gives us an idea of the astounding growth of the Amish romance novels in the publishing market:

Sales numbers and bestseller lists confirm the vigor of the Amish-fiction category. The triumvirate of top Amish romance novelists—Beverly Lewis, Wanda Brunstetter, and Cindy Woodsmall—have sold a combined total of 24 million books. At least seven of Lewis’s Amish novels have sold more than 500,000 copies each, and one of those, The Shunning, has sold more than 1 million copies. Brunstetter’s fifty books, almost all of them Amish titles, have sold nearly 6 million copies. [Pg. 5]

I agree that hypermodernity and hypersexualization are two reasons why people are drawn to the Amish in general and to the Amish romance novels in particular. I would add another aspect, which Weaver-Zercher named but did not define or give as much attention as the other two: hyperindividualism. I feel this cannot be underestimated. In mainstream culture, we are taught that if we want something badly enough we can either achieve it or acquire it. We think if only we had enough money, then we could have anything we want. We isolate ourselves with screens in front of our faces how many hours per day? For however long it is, we are not interacting with other people during that time, which means we’re sacrificing community. We cannot possibly have meaningful interpersonal interactions in a community setting and be in our own world, too. People try, but they don’t succeed. It seems unplugging and living a simpler life is not as easy as reading an Amish romance novel.

Weaver-Zercher’s best example of this phenomenon is Suzanne Woods Fisher, host of the Toginet Radio show Amish Wisdom, who invites her listeners to “slow down, de-clutter, find peace, and live a simpler life” each Thursday afternoon. However, Fisher’s life is anything but simple. She is the author of numerous Amish books and is contracted with her publisher, Revell, through 2016. In 2012, she had ten books on the market with eleven in the works. In one particular busy stretch, five of her books appeared in seven months. She writes them at about the rate of one every three to four months.

Besides being a radio host and author, Fisher is mother of four children and she has a little grandchild, a dad with Alzheimers and a mother who needs lots of help. Her husband is a finance executive who travels frequently. It is Fisher’s hypothesis that Amish fiction is “a response to the feeling people have of being out of control with technology and change that is coming so fast. The feeling that you have a cell phone and you are never off the hook, you are responsible to be available all the time—it’s just overwhelming. I think there’s a longing for a life in which you’re unhooked and detached, and we can’t do it; it’s too hard.”

The irony of “fast texts about a slow culture” is not lost on Weaver-Zercher. Several authors are contracted to write at least two books per year, besides Fisher writing at least three per year. So the people who want to read Amish books to fantasize about slowing down their lives are causing the already hyper capitalist publishing industry to go into overdrive. This is one of those incongruities of Amish romances.

I thought that Beverly Lewis pioneered the Amish romance novel when she wrote The Shunning back in 1997. However, Weaver-Zercher points out that there were several antecedents, including Sabina: A Story of the Amish by Helen Reimensnyder Martin published as early as 1905. She names at least five others. From reading Thrill of the Chaste, it is clear that Beverly Lewis came out with The Shunning at the right time—the market was ripe for an Amish story.

As I was reading Thrill of the Chaste, I kept feeling that Weaver-Zercher was missing something vital in her study. I wanted, in the worst way, for her to analyze the accuracy, or more precisely, the authenticity of the Amish romance novels. Finally, on page 197 (of her 250-page book), she addresses this when she writes: “To what extent terms like authenticity and accuracyeven matter to most readers of Amish fiction is uncertain.” A paragraph later, she writes that the most frequent inquiry she received from people is how accurate are these novels. I would assert that if this was her most frequent inquiry, then it does matter to people. And then the truth comes out in her description of her response, “Whenever anyone asked me whether Amish novels are accurate… I usually mumbled something vague and entirely unhelpful…. I doubt I gave anyone the answer they were looking for, partly because I wanted to argue with the question.”

It seems the reader may not have gotten any idea of Weaver-Zercher’s feelings about authenticity in the Amish novel, had it not been for her friend Richard Stevick, who one day told her she must deal with this question of accuracy.

And so for the following chapter, Something Borrowed, Something True, Weaver-Zercher finally does write about the lack of authenticity of some of these stories, though she often puts the criticism in others’ voices, including mine. (She quoted from my blog post

Amish Fiction).

Weaver-Zercher then asserts that most inaccuracies are generally invisible to anyone outside a relatively small crowd of Anabaptists or their friends, and that it is likely that Amish fiction clears up more popular misconceptions about the Amish than it creates. And then she asks, “And if readers walk away thinking that the Amish in Lancaster County drive black buggies instead of gray, or that Amish people write letters in Pennsylvania German rather than English, has any real harm been done?”

Then Weaver-Zercher writes, “novelists cannot be released from all responsibility to the actual world, however, especially when they’re writing stories about a living ethnic and religious culture to which they and most of their readers do not belong. Representing one culture to another comes with a host of ethical responsibilities, and the ancillary dangers—circulation of misinformation, appropriation of cultural symbols, assertion of control—are many.”

This would have been a wonderful passage with which to start a book about Amish romance novels, but that would be a whole different book. Being it is so close to the end of the book, it hasn’t been part of the discussion from the start. I find it so very inadequate and incomplete.

I would say no, there isn’t any real harm done with the inaccuracies of the different color buggies or what language letters are written in. But when an author and her readers superimpose their values on the Amish, then I believe there is real harm done. Because I am not writing a book-length review, I will focus on one real way I feel harm is done.

In these novels, the protagonists become a born-again Christian, and by doing so, they are now saved through Jesus Christ, something the “works-based” or “rules-based” Amish religion could not do, is the implication.

According to Weaver-Zercher, some of the upcoming Amish fiction will be super-charged with this message. One author said that she is writing Amish fiction, “To expose the Amish lifestyle as, not Christian, but a cult. They are a community of ‘works get you to heaven,’ not salvation through Jesus’ atoning work on the cross alone.”

I groaned when I read this. During my book talks, I have encountered people in my audiences who ask, “Is the Amish religion faith-based or works-based?” To which I will reply, “Both.” Sometimes they think I misunderstood the question and rephrase it, “Well, what I mean is, do they believe in salvation through Jesus Christ or through good works?” To which I will again reply, “Both. They definitely believe that Jesus died on the cross so that they may have everlasting life, but they also believe that following Jesus’ example in doing good is important in their life on earth.”

One day on our way home from a book talk my husband, David, asked, “What is wrong with good works anyway?” My guess is that many born-again Christians would say that if you believe in good works, then that excludes the belief that Jesus is your Savior. What they don’t realize is just how much they are misunderstanding the culture they are judging and that it doesn’t have to be one or the other and by thinking it is, they are limiting themselves from gaining a better understanding of the Amish people and their tenets.

Another deep misunderstanding in Amish romance novels, when a protagonist decides she needs to leave the Amish she does so with apparent ease. What they miss completely is something so obvious to someone who has left the Amish… no matter the reason for leaving or how sure we are that the decision we made is right, we all have to deal with the loss of community that comes of leaving. For an example of the turmoil that one feels when caught between two worlds, you can read my earlier posts

Anna’s Return, and

A Letter from Anna.

It is tempting to blame the Amish for shunning their family members who leave. But they would not be Amish if they didn’t use shunning as a church discipline. I believe that the cohesion in a given community is commensurate with the level of sacrifice and effort people need to make to be a part of that community. The Amish have a sense of community the rest of us can only admire or envy. They value community over the individual, which is the reverse of our culture in which individual freedom (often in excess) is valued over community. And the Amish teach that you are either Amish or you’re not—there is no in between. So you cannot have it all.

This is one way in which I feel the Amish are completely misunderstood by the authors of Amish romance novels. I will save their misrepresentation of what they call “pow-wowing” for another day. And rumspringa—I’ve already written extensively on that.

Weaver-Zercher writes about the Amish romance novel transporting the reader to Amish country, “Now, thanks to Amish fiction, America’s own exotic but homespun religionists are as close as the book on the bedside stand.”

I would argue that the Amish romance novels feed the American fantasy that we can have it all—we can keep up the fast pace of our lives and at the end of the day, we can pick up a book and be transported to the rural landscape of Amish country—all without sacrificing anything aside from the time it takes to read the book. It seems to me that this is as momentary as eating candy… it tastes good, but there is no lasting nourishment in consuming it. Furthermore, there is something wrong with appropriating the Amish culture for our amusement.

I wish Weaver-Zercher would have addressed one very important point. The authors of Amish fiction want it to have it both ways—they want to use the Amish culture as backdrop for their novels, while at the same time judging the Amish beliefs as being inadequate for their salvation. Furthermore, they are making a personal fortune by doing so. You don’t have to be born and raised Amish to understand these incongruities.

If I didn’t have to read a bunch of the novels that would certainly give me literary indigestion, I might want to write a book about the myriad of ways in which the Amish are misunderstood, misrepresented, exploited, and appropriated in Amish romance novels and how they set the stage for even greater lies about the Amish culture in reality shows like “Breaking Amish” and “The Amish Mafia.”

Weaver-Zercher’s book Thrill of the Chaste is a good first step in understanding our fascination with the Amish. I would assert that there are deeper reasons for this fascination. We know, deep down, we need something that the Amish have. To be a part of an Amish community, one has to practice self-denial, humility, and austerity and yet we, of the world, don’t want to deny ourselves anything. We sense the divinity in Amish people and even how they achieve it, but we refuse to follow their example. In Suzanne Woods Fisher’s words, “It’s just too hard.”

Write the book Saloma! A book about the truth of Amish culture/religion written by a former Amish person would interest many, although I think we both know that most people don’t want the truth. They want a reprieve from their hectic lifestyle. I personally enjoy fairytales (even though I’m fully aware that a medieval princess’ s life was typically not so romantic) and I think Amish fiction is some people’s version of a modern day fairytale.

I also enjoy memoir. I feel memoir gives me a more accurate view of other cultures and lives, which is why I enjoyed your book “Why I Left the Amish”.

Keep up the great work with your blog. The people who want the truth will eventually find it and your blog is one source for that.

Saloma,

There is so much here to digest. Wow!

I have so many questions. Who is buying these Amish romance novels? What is the average age? Race? Where did they grow up? What religion, if any, are they? Do they read strictly Amish romances? If so, why? Level of education? Married? Single?

I think the Amish are exploited, in a big way, through these romance novels. If the writers gave a chunk of the royalties to the Amish community, anonymously, to fatten up their medical/emergency fund, I would think twice about that, but who is honorable amongst them?

I have only one gripe about the Amish as far as their “philosophies” go. They tell their kids they will burn in hell if they leave the Amish culture. That is beyond wrong. That’s going against what God says.

“Faith without works is dead.” The two go together, but only one allows a person into Heaven.

Keep writing, dear lady. You keep my wheels spinning.

Hi Saloma,

There is a lot to chew on here. Wow!

I think the Amish culture is exploited through Amish romance novels. Not only through a lack of clear facts, but because they just want to be left alone. But I suspect most of them don’t give a rip what rubbish people are writing about them. That’s one of the fringe benefits of being Amish. You get to ignore the idiocy of the world.

Wouldn’t it be nice if some noble, honorable, Amish romance writer would anonymously fatten up the medical/emergency fund of a few of the communities they reap so much from? Fat chance!

The only gripe I have with the Amish culture is that they teach their children they will burn in hell if they leave the fold. That is beyond wrong. The thing is, do those saying it really believe it? If they do and one of their children leaves they are destined for a life of perpetual hell here on earth. What parent wants their child to live in torment forever? And what child wants this for himself? If it were not for this, I would have the utmost respect for the Amish.

Interesting article, Saloma. I am now in my mid70s and haven’t been Amish since I was 17. Although I am an avid reader of all sorts of material I have never read Amish fiction- oh, wait- I think I read one called Rosanna of the Amish or something like that, many years ago. If I read it, I no longer remember any of its details.

However, I have two sisters, both in their late 80s- and they read these stories. Since I live in Alaska and they are in Oregon I have never seen any of their books, but my sis has told me that there are many errors in most of them, especially regarding ‘rumspringa’. I must say that until I heard it on television I had never heard of the ‘English’ version of rumspringa. We must have been pretty tame. lol

I am enjoying reading your accounts of ‘Amishness’ and applaud you for staying so true to facts.

Elva Bontrager

Interesting article, Saloma. I am now in my mid70s and haven’t been Amish since I was 17. Although I am an avid reader of a great variety of material I have never read Amish fiction – oh, wait, I may have read one called Rosanna of the Amish or something like that. If I read it, I no longer remember any of its details but I remember the cover: it was blue and depicted an Amish girl with a white ‘covering’. Funny how memory works.

However, I have two sisters, both in the late 80s and also no longer Amish although one is Mennonite, who do read those books. Since I live in Alaska and they are in Oregon I have never seen any of their books but my sis has told me that there are many errors in them, notably regarding ‘rumspringa’. (I must say I had never heard of the ‘English’ version of rumspringa until I saw it on TV- we must have been pretty tame. lol)

I am enjoying your accounts of your journey through life and applaud your dedication to truth.

Elva Bontrager

What’s your view of Amish novels written by former Amish people? The Lily books (Joyful Chaos) come to mind … of course, they’re written by someone who had roughly the same religious experience you seem to disparage as part of her exit from the community…

I honestly have not had the chance to read the Lily books. From the excerpts I’ve read online, they are good children’s books. I think Mary Ann Kinsinger is a fabulous writer, and she is not going to get the details wrong. That in itself is more than I can say of the authors reviewed in Weaver-Zercher’s book.

I don’t disparage anyone’s experience who ACTUALLY left the Amish… I have a problem with the same outcome in every Amish novel… not everyone has that experience when they leave the Amish.

Saloma

I think people read the Amish Romance as pure escapism and nothing more.

I read a few of the Lewis books about five or six years ago, to see what all the fuss was about. I thought they were rather silly, the characters very one dimensional, the story line/plot formulaic, and the books filled with feel good imagery of warm cozy kitchens, fresh baked cookies, etc. etc. Pure escapism.

Kind of like British detective shows, Miss Marple, Inspector Poirot, Inspector Morse, they have really very, very improbable story lines, but the imagery and scenery/sets are very cozy and candy for the eye. In fact the British have a name for these types of novels/shows, they call them cozies!

Although this is an old blog entry, I would like to add my two cents: As a Catholic (who happens to live in Indiana’s Amish country), I find the idea of these evangelical novels about the Amish to be deeply offensive. I have seen such novels in the bookstores around here. I had naively assumed that they were simply romance novels set in the Amish community that portrayed Amish women falling in love with Amish men. I should have known from the fact that I especially see them in “Christian” (that is, evangelical) bookstores what they would be. It is only because the Amish are more “colorful” than Catholics that there is not a similar line of “Catholic” romance novels for evangelical Christians. (Actually, for all I know, there may be, along with “Mormon” romance novels.) Like Amish novels, I’m sure they would always have the protagonist leaving their childhood faith for “real” evangelical Christianity, because that is the only way, from an evangelical perspective, to have a happy ending. This is their belief, and it is their right to spread it to one another, and to whomever else wants to listen. However, I would like to see more “push-back” by those of other persuasions. I suspect too many people pick these books up naively, and swallow what they read hook line and sinker. No one speaks up in public and says “These books are an evangelical effort to say that there should not be any Amish, or anything else but evangelicals. If you don’t believe that and don’t want to make people rich for saying it, don’t buy them.”

Pingback: About Amish | Amish Conference 2016, Part 2

Pingback: Trad wives hearken back to an imagined past of white Christian womanhood – Johansen.se